I was recently reminded of Tim Gallwey’s ** performance equation : Performance equals Potential minus Interference.

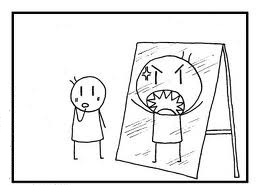

Although a tad pseudo-scientific, Gallwey’s equation succinctly expresses the notion that most of our battles are not ‘out there’ but in our own heads – how we play our ‘Inner Game’. The issue is not what we can do, so much as what we talk ourselves out of doing. Just listen to your own self-talk next time you face a difficult or challenging task and you will probably hear self-doubt, negative forecasting and other forms of self-limiting beliefs – all examples of ‘mental interference’ in Gallwey’s terms.