Boundaries seem to have a bit of a bad press – they suggest no go areas or ‘thou shalt not’s’ – and are a bit anathema to conventional coaching which is often about dismantling personal limitations and self-imposed restrictions.

I’ve had a suspicion for a while that managing change in organisation is actually often about managing anxiety levels. Just watch your own heart rate go up in a meeting when ‘hot words’ like ‘redundancy’, ‘restructure or ‘pay freeze’ get bandied about.

I had a lovely piece of feedback today to the effect that I designed and ran development programmes where people actually applied their learning in their real worlds and experimented with changed behaviours.

Whilst not averse to a compliment, what struck me most about this comment was that it needed to be said at all. Surely we don’t run development programmes for the good of our health? What other walk of life would we invest our time, money and effort and not expect to get some sort of return or benefit. When did it become OK to go on development programme and leave the learning to gather dust on the proverbial shelf. While I get that there may be barriers to applying training messages (time, relevance etc) it does seem to have become normal not to expect much out of a course or that it somehow doesn’t apply to us personally – and hey presto we have a self-fulfilling prophecy in action. I also think – while I’m on the subject – that we training designers need to get way more creative and that the ritualised action planning session we habitually include in the last hour is just not enough to ensure application and transfer.

We spend literally billions worldwide on training and development – are we just wasting out time and money or have we (trainers and trainees alike) just forgotten how to take development seriously? OK rant over

.

OK gross generalisation coming up – I meet two types of line managers .. those who take way too much responsibility for their people and those who take too little.

My first type can really go over board with this even to the extent of feeling responsible for the emotions of their staff and holding sense of failure if everyone is anything less than happy and content. This can result in leaders who fudge feedback, struggle with the difficult conversation or (just) spend their spare time in a state of angst. Not good for them and probably not good for their people either. Coaching this type of leader often involves getting them to see that they have reasonably done all that that they should do and separating out a little from the emotional life of their team.

My second type tends to hold relationships at work at some distance and often have problems reading where other are coming from . They don’t see that they are part of the life of the team and like it or not do a lot to set the tone and climate in the workplace. It can be a considerable shock for them to find that there is something of a gap between their intent as a leader and the actual impact they are having. Coaching this type involves strengthening the empathy ‘muscle’ and getting them to use feedback to monitor and manage the intent/impact gap.

So .. what sort are you? Do you take more or less than your 50%?

I met Roger (not his real name) last week. I was facilitating an intensive workshop for a large group of very disgruntled managers. They had all been through the mill, bruised survivors of a protracted change process which had left them with roles and responsibilities they didn’t fully understand, and weren’t they wanted. Roger was typical – there was nothing anyone could say or do that would convince him the changes had been of any benefit – and he fully intended to carrying on working as he always had (thank you very much). The management team, increasingly frustrated with his intractability, were running out of ideas on how to convince him.

I recently had the pleasure of listening to the provocative and insightful Professor Ralph Stacey – prolific writer on the complexity sciences and leadership and management.

He was talking about he experience of lecturing to a class of 100 students and asking them to write an assignment on what he had just conveyed … and the frustration of getting 100 very different answers back. “The logical conclusion” he said ” is that either I am a very bad teacher or I have 100 very stupid people in my class”, neither of which were particularly palatable or likely explanations. Instead of getting frustrated he now thinks this ‘failure of communication’ should be expected and maybe even welcomed. After all 100 people will all have their individual ways of making sense depending on their very different experiences and interests – none of us are blank canvasses.

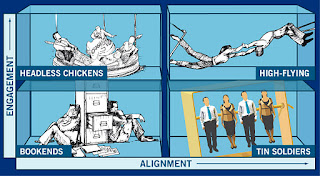

I was thinking about this in terms of communication processes in large organisations and the frustration I meet in leaders who say “I’ve told them, but they still go off and do their own thing”. Stacey’s point is that communication is not a simple process of transmission and reception (radio metaphor) but an interaction where both parties make sense together, both influencing and being influenced, the final message emerging out of the exchange. 100 people are bound to hear 100 different messages, particularly when exchange is limited or constrained. Perhaps we would have less compliance issues in organisations if paradoxically there was less dependence on ‘tell’ and more on ‘engage’, less reliance on email and more on old fashioned face to face conversation. It will never catch on!

I was recently coaching a team and used an old favourite of mine – the ‘shared history’ – as a way of catching everyone up with the ‘story’ of the team. It involves sitting everyone in the order they joined the team and briefly telling the tale of how they came to join and what was going on at time. What usually emerges is a rich picture of the team’s back story which gives a sense of the struggles and successes to date as well as the personalities involved.

The exercise had the reaction I often get – the old hands are amazed at how much water has passed under the bridge – “I’d forgotten about ….I hadn’t realised how much we’ve done!”. The new joins are mightily relieved to get a handle on the context they now find themselves operating in and why things are the ways they are – “It all makes a whole lot more sense now!”

The membership and purposes of a team are always shifting yet we often talk and act as if a ‘team’ is a static entity. How would it be if we considered the team to be new team every time a new member joined? What would it take to pay more attention to their integration and assimilation into the team story?

I spend a lot of time working with managers on their coaching skills and encouraging them to take a coaching approach to their leadership, and have become increasingly fascinated by resistances to coaching in managers. While pretty much every manager I meet want lee way and personal discretion in how they operate .. however… this doesn’t necessarily extend to their subordinates. “They just want to be told ..none of this dancing around the handbags asking questions” they report emphatically.

Where is reality in all of this? Do subordinates only want to be told or do managers enjoy telling too much? I know there are times when I need and welcome direction however someone being directive (ie overly controlling) will generally get my hackles up. Mostly I want space to think and act for my self and yes I want someone to consult with just in case my ideas are flawed or too limited. I also know that different people have different needs for elbow room – some folks seem to need acres of personal discretion while others are anxious with anything less than close marking

Part of the issue I think is that it much easier to think about leadership in binary terms – I tell or I coach, I give direction or I consult. What is far tougher … but vital…is to be choiceful in approach to people management. One style does not fit all situations and reading the situation to make an informed choice of what is required is skill that can be developed.

(Thanks to the work of Emery, Trist et al)