I work with a lot of leaders to help them develop and hone their coaching skills. A common misapprehension amongst them, especially in the early days, is that coaching is some sort of cosy supportive relationship — usually involving a lot of open ended questions and not a lot else. The phrase ‘pink and fluffy’ comes to mind.

|

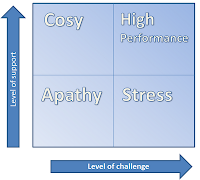

| Daloz’s Support & Challenge model |

While I do believe part of the role of a Coaching-Manager is to support their team, I also believe that they are there to challenge them to do more and continuously raising the bar. The balance of support and challenge is therefore crucial to effective coaching – too much support and coaching becomes a cosy chat, too much challenge and the team will head for the hills. This is a case of ‘and’ not ‘either/or’. When the balance is right, coaching is both fun and stretching, working right at the edge of what is possible.

Coaches and Coaching Managers therefore need to know which they find most challenging – being supportive or being challenging – and learn ways to ensure they bring both into their work in the right quantities and at the right time. No challenge there then!

Source: Daloz,L. (1986), Effective teaching and mentoring: realising the transformational power of adult learning experiences.